The Survival of Pat Dugan

December 7, 2007

By: Bill Sontag

Courtesy of the former Del Rio Live internet site.

Pat “Pitbull” Dugan, Class of 1964, is an unrepentant “recon Marine” firmly planted with deep roots in his hometown of Del Rio, swearing he’s here for good. Dugan has seen enough of the bad in other, remote parts of the world, and believes there are lessons there for anyone concerned enough to “Brighten the corner where you are,” as an old hymn suggests.

“There’s a big difference between being a combat person and a non-combat person,” explains Pat Dugan during his LIVE! interview. “I’m a marine, and I’m proud to be a marine, but I’m even more proud to be a combat marine.”

He has his heroes, but doesn’t want to be thought of as one. He has his enemies, and doesn’t much give a damn about them. But Pat Dugan, affectionately known to himself and others as “Pitbull,” zealously guards a belief system of fearless integrity, spilling out as an anthology of adages and quotes.

“I’m a grunt. A grunt is a guy who gets up every morning, and throws the dice with God,” Dugan cracked, Wednesday (Nov. 21). And of his 19 months of service – 1966-1968 – as a reconnaissance Marine corporal in the jungles of Vietnam, Dugan is emphatic: “I don’t consider myself a hero in any way, shape or form. I’m somebody who was able to rise to the occasion, and survive it.”

Vietnam was not the first challenge to which Dugan rose, and it certainly was not the last, but the war in Southeast Asia affirmed and honed skills and the life lessons that fostered them. Dugan’s paternal great grandfather, Frank Anthony Rose, was a Texas Ranger stationed at Fort Clark, and his grandfather, Frank J. Rose was the Brackettville sheriff and entrepreneur who also owned the Blue Goose Saloon.

Dugan’s father, Charles D. Dugan, served as a survival instructor in the U.S. Army Air Corps. “He escaped and evaded his way out of the Po Valley [Italy, 1945], and he taught me to never use a map. So I learned to navigate with a wristwatch and a compass,” Dugan said, adding that landmarks are only potentially confusing, and that use of maps and landmarks will attract “an enemy who will find you and kill you.” The lineage of tough, savvy men – Dugan’s progenitors – ends here. “My dad flew into Laughlin with the fifth B-26 bomber to arrive here during World War II.”

Dugan’s matriarchal side includes Del Rio pioneer Pietro “Red Beard” Gerola, his great great grandfather who came to Del Rio from Milan with several other families in 1882. The Italians came to build and create commerce. Architect John Taini designed and built many of Del Rio’s elegant limestone homes and downtown retail buildings. The Qualias, Serafinis and Gerolas chartered and leased 80 acres of land from Doña Paula Losoya Taylor to create the Val Verde Winery.

Dugan had deep roots in Del Rio, but a father who traveled the world for the U.S. Air Force, so it’s a wonder that Dugan grew up here, left, and came home again with such gratitude that he swears he will never leave. While he and his family lived on Fourth Street – a crossroad between the Comalilla neighborhood and the Chihuahua barrio – Dugan graduated from Del Rio High School in 1964, briefly and unhappily attended Sul Ross State College, and joined the Marines. Del Rio war hero Alfred Lay was an inspiration. “He was why I wanted to be a Marine,” said Dugan. “My Uncle Rudy Rose ran the Four Roses Bar, and I used to see Lay come in in his uniform. He was in the third assault wave at Iwo Jima, and when I came home from Vietnam, he took me under his wing, and kept me from doing all the bad things I was going to get into,” Dugan said.

With sturdy, ancestral stock as a foundation, local heroes as inspiration – and unshaken by a father who thoroughly and violently disapproved of his son joining the United States Marine Corps – Cpl. Charles Patrick Dugan rather suddenly found himself in 1966 on a cold, fogbound mountaintop near the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Vietnam. Struggling with his comrades to celebrate Christmas Eve under conditions that had nothing to recommend it, Dugan and the rest of Company K (Tango Security Group), 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marine Division were demoralized, bogged down in mud, festering with intestinal disease, and living in damp, cramped sandbag bunkers.

Years later, Dugan told Del Rio News-Herald writer Dennis Smith that his platoon buddies were desperate to mark the traditional evening: “Nobody ever mentioned what to do, but everybody had a flare, and at midnight, everybody’s bunker shot a flare up. It was the most beautiful sight I think I’ve ever seen. There we were, out there in the middle of the jungle on top of this hill, and all those flares were coming down, and all over you could hear Marines singing Christmas carols. It was pitch-black dark with fog, but you could hear those Marines singing. The enemy must have thought we were crazy!”

Sgt. 1st Class Charles D. Dugan, second from left, poses with B-26 “Marauder” crew members during World War II. Dugan, a survival instructor in the U.S. Army Air Corps, put those skills to use when his bomber crashed in Italy’s Po River Valley behind enemy lines, escaping capture and guiding his crew back to friendly forces. Dugan was furious when his son joined the U.S. Marine Corps, but had instilled in him the very temperament and knowledge that would ensure Cpl. Pat Dugan’s safety and success in Vietnam.

Sgt. 1st Class Charles D. Dugan, second from left, poses with B-26 “Marauder” crew members during World War II. Dugan, a survival instructor in the U.S. Army Air Corps, put those skills to use when his bomber crashed in Italy’s Po River Valley behind enemy lines, escaping capture and guiding his crew back to friendly forces. Dugan was furious when his son joined the U.S. Marine Corps, but had instilled in him the very temperament and knowledge that would ensure Cpl. Pat Dugan’s safety and success in Vietnam.

The northern segment of South Vietnam where it bumps up against the so-called Demilitarized Zone was geography identified as “I Corps.” An anonymous Marine Web site says of the region, “The terrain within I Corps favored the enemy. The rugged, jungle-blanketed mountains that cover the western pan of the region hid Communist supply bases and the camps of main force units and facilitated the infiltration of North Vietnamese replacements and reinforcements.”

Most of Dugan’s year-and-a-half “in country” was spent on Hill 724 in the Hai Van Pass, aptly named, Dugan said, meaning in Vietnamese, “a place in the clouds.” “We were way up north, where the rubber meets the road,” Dugan said. His platoon was a hand-picked group of Marines chosen for their skills and perseverance, qualities needed to protect an important missile battery. The HAWK, an acronym, Dugan said, for “Homing All the Way Killer” was a highly-valued potential defense weapon, a surface-to-air missile to follow and take down enemy aircraft or launched missiles. The Marines introduced the missile to Vietnam, and were the last units to remove them, but it’s believed they were never fired in combat because of America’s air superiority.

He was trained to use an M-60 machine gun, but found its size and long range both cumbersome and useless within the dense triple canopy of jungle that covered the mountains like a shroud. He resorted to carrying a shotgun, far more effective at the short range in which he was likely to confront enemy. But his job was intelligence, gathering information. “A reconnaissance Marine goes out and finds the information to save lives. Where the enemy is, what is their troop strength, what are the natural hazards between your unit and them, these are the things we needed to know and report,” Dugan said.

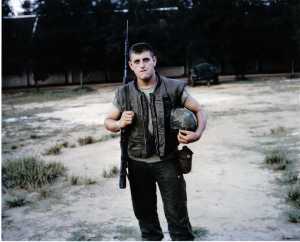

Cpl. Pat Dugan stands in the ruins of an abandoned French Foreign Legion fortification during the Marine Corps and Army of the Republic of Vietnam sweep, July 1966, to secure part of the Quang Tri Province in the Demilitarized Zone. The mission was dubbed “Operation Hastings.”

Cpl. Pat Dugan stands in the ruins of an abandoned French Foreign Legion fortification during the Marine Corps and Army of the Republic of Vietnam sweep, July 1966, to secure part of the Quang Tri Province in the Demilitarized Zone. The mission was dubbed “Operation Hastings.”

The information was collected on patrols, usually no more distance than 3,000 meters or about 1.75 miles. “But that might take you eight hours, and it was work in that vegetation. I was in a jungle where you didn’t see the sun for days. And you learned to never walk on trails,” Dugan said, explaining that such thoroughfares were almost certain death traps. Dugan preferred night patrols, explaining that the Marines moved carefully at “nautical twilight” (with the sun below the horizon, but not so far that the horizon was not discernable) into a “hide,” a place of concealment as darkness approached, knowing they were probably watched. Then, in darkness, they’d move and begin their reconnaissance efforts.

“Every night in that jungle, I had to rearrange things in my mind to survive. And that’s a good lesson for the rest of your life. In daytime, we owned Vietnam, but at night, they owned it,” Dugan said. He called the rearrangement “putting certain things in little steel boxes in my head.” He learned a thousand skills to blend into the jungle and to court the rustic populations in small villages that dotted the hillsides. “I ran into woodcutters all the time, cutting wood and taking it to sell in villages. I wanted to learn that jungle, so I’d give them cigarettes, help their kids get medical treatments, and gave them candies.

“I was nice to the kids, so – sometimes as I was leaving a village, the mamasans, the mothers, would warn me, maybe just with their facial expressions, ‘No, don’t go that way; go this way,’” Dugan said. “Because they wanted me to come back. I loved those villagers. I treated them with courtesy, dignity and respect, and – guess what – I’m still alive,” Dugan quipped. “They loved menthol cigarettes, but I learned to smoke Ruby Queens [Vietnamese cigarettes], because when you’re out there in the woods, you can smell American tobacco a mile away.”

A portrait of toughness and resolve, the Del Rio marine’s training and weaponry on a rocky Vietnamese mountaintop illustrates a Dugan aphorism: “It’s OK to have a lion’s mouth, as long as you don’t have a canary’s ass behind it.”

Dugan also developed a taste for pressed fish oil in his diet to better blend in with his subjects. “I smelled like them. I smoked like them. I thought like them. To get good intel, you’ve got to have the respect of the people you’re talking to, and I knew those woodcutters knew and had what I needed to come back to Del Rio,” Dugan said, describing his gentle approach – cultivating friends in entire villages, gathering information and staying alive by following a Marine adage: “Adapt, improvise, overcome.”

Dugan is unimpressed with the style of village and city streetfighting he sees American troops practicing in Iraq. “I’m watching bad infantry on TV every night. Every time you kick down a door, you’ve made five more terrorists,” Dugan said.

In Vietnam, Dugan was injured many times, but he deflects questions about it. He was awarded medals, but is disdainful of those who show them off. There is one exception. Dugan worked in Vietnam with Vietnamese Marines for whom he has an abundance of respect. His demeanor and accomplishments were rewarded three times with that country’s highest honor, the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry. “I like the Vietnamese, and I got along well with them,” Dugan said.

When he finally returned to Del Rio by bus, Dugan asked bus driver Dean Forth to pull over beside San Felipe Creek. “I got out, and splashed some of that water over my face, and baptized myself and swore I’d never leave home again.”

“Mamasan,” one of Cpl. Dugan’s cultivated friends pounds grain in a village kitchen area. Dugan respected and nourished positive relationships with villagers in continuing efforts to stay alive and to gather information important to his reconnaissance forays on night patrols.

“I fell in love with the jungle of Vietnam, but was very frustrated because I didn’t know what was there,” Dugan said by way of explaining his choice of a curriculum in wildlife biology at Stephen F. Austin University when he returned home in early 1968. “That was a tough time, though, because of the anti-war movement on campuses.”

He recalls a smarmy political science professor who began his semester introduction to the class, asking, “How many of you are in here on the free lunch program?” The transparent jab at veterans pricked Dugan’s ire. “I was in trouble, because I stood up and said I wanted a favor, and – in baby talk tone – he asked me, ‘Oh, are you going to ask me to be nice to you?’ And I said, ‘No, it’s just going to take a minute for me to get down there to kick your ass! Well, he ran out the door, and left his hat right there on the desk.” The dean of the university was a former Marine, so Dugan was counseled rather than expelled. “But I was a recon Marine, had just gotten back from overseas, and I was just in no mood to put up with that,” Dugan said.

Dugan was very close to Del Rio’s extensive Calderon family, and in 1969, Dugan got a phone call from Del Rio’s famed educator and mentor to children Dr. Fermin Calderon who invited him to return to Del Rio to march, arm-in-arm with him in a civil rights march here. “Dr. Calderon was like a father to me. He got me into the American G.I. Forum Golden Gloves boxing program, and I came at his request to march with him.”

In 1971, Dugan started teaching eighth- and ninth-grade English at San Felipe High School, and, while teaching, also worked for the Bureau of Prisons. He became assistant principal of Del Rio High School, and 1993-1996 Dugan served as the principal. During much of this time, 1971-1991, Dugan quietly served his beloved Marines as a civilian advisor for the 4th Reconnaissance Battalion Marines, San Antonio, as they launched “Operation Border Eagle,” a clandestine exercise for drug and smuggling interdiction with the U.S. Border Patrol and the federal government’s Joint Task Force Six, headquartered in El Paso.

HAWK surface-to-air missiles stand perched atop Hill 724 in the Hai Van Pass guarded with both reconnaissance and perimeter defense by Dugan and his fellow marines. Because of United States’ air superiority, the missiles were never used in combat to strike down enemy aircraft.

Dugan was commended for his continuing work – “Once a Marine, always a Marine” – so stated by Gen. A.M. Gray, commandant of the Marine Corps. “That tradition holds true as evidenced by your continued loyalty to our Corps,” wrote Gray to Dugan in a personal thank-you letter, April 2, 1990.

Dugan’s no-nonsense approach to kids while he was principal of Del Rio High School seemed sensible to the student body, but not to his superiors. “The students seemed to like me,” Dugan said, “but not the administration.” From June 23, 1997 to Aug. 4, 2000, Dugan served as chief deputy to Val Verde County Sheriff A. D’Wayne Jernigan.

Tuesday (Nov. 27), Jernigan told LIVE! “He had a way of getting the kids to do what they had to do. My stepson, Anson Luna, was at the high school when Pat was principal, and he just thought that Pat hung the moon. I believe most of the kids just loved him. I know Anson had the utmost respect for him.” Luna, Jernigan added proudly, is now a special agent for U.S. Immigration & Customs Enforcement, McAllen, Texas.

Dugan now lives quietly with his wife, Phyllis, and the couple are proud parents of three daughters: Cayton Janner, Austin, Carlyn Pfeuffer, New Braunfels, and Cathey Rose Dugan, Africa. Dugan’s devotion is also directed at Cpl. Jack Russell Dugan, his terrier, also known as Cpl. J.R. Dugan has been partial to small dogs since he took a brown puppy away from a Vietnamese villager who was raising the mutt (later to be dubbed Cpl. Brown Dog) to be eaten.

Cpl. Pat Dugan’s home a long way from home, a sandbag bunker, provides a view over the mountain jungles of the Hai Van Pass. Fog shrouded the mountains, often marginalizing the observation of enemy movements. At night, only flares popped skyward could reveal incursions that often resulted in sudden, terrific battle.

Brown Dog saved Dugan’s life and most of his platoon when he went “on alert” in the bunker, Dugan fired flares, and found a horizon filled with enemy coming through perimeter defenses. During a bitter firefight resulting in many deaths and injuries on both sides, Brown Dog was badly injured, but considered a hero, put on a medevac helicopter and saved by U.S. Army veterinarians.

Dugan has the same fealty and love for Cpl. J.R., and insists that both are to be cremated, ashes saved until both have been put in a single urn, and – shaken, not stirred – to be certain the ashes are well-mixed before scattering.

Meanwhile, Dugan’s Saturday morning treat is breakfast each weekend with Lalo Calderon, Phyllis, Al Birkhead and a coterie of friends and colleagues at México Típico Restaurant on Dr. Fermin Calderon Boulevard, the thoroughfare named for Lalo’s brother and Dugan’s mentor. But in his private moments, Dugan is still opening and dealing with the contents of those troublesome “little steel boxes.”

Dugan is snapped by a press photographer during a patrol on Hill 724 near the Demilitarized Zone of northern South Vietnam.

Dugan is snapped by a press photographer during a patrol on Hill 724 near the Demilitarized Zone of northern South Vietnam.

Cpl. Jack Russell Dugan, USMC, 2164539, is Pat Dugan’s much-loved canine shadow on walks in local cemeteries and Lions Park, Del Rio. In 2005, Cpl. J.R. and Dugan walked in Sacred Heart Cemetery when the terrier bolted toward a grave, scratching away leaves and detritus. The pooch had mysteriously uncovered a grave marked, “Jack A. Russell, Texas, Cpl., Signal Corps,” honoring a Korean War veteran.

“Once a marine, always a marine.” On paper, Cpl. Pat Dugan is retired from the U.S. Marine Corps, but he has no interest in putting his military training, experiences and patriotic philosophy on a shelf.

In fact you can follow Pat on Twitter!